Review

Deformity Reconstruction Surgery for Blount’s Disease

Blount’s Disease, also known as tibia vara, occurs due to a partial growth arrest of the medial proximal tibia either during infancy, mid-childhood, or adolescence. It is therefore often referred to as infantile, juvenile, or adolescent Blount’s disease, respectively.

The most obvious characteristic of Blount's Disease is the varus of the knee, a deformity in which the knees bow outward in relation to the pelvis. This deformity is also referred to as Bow Leg Deformity.

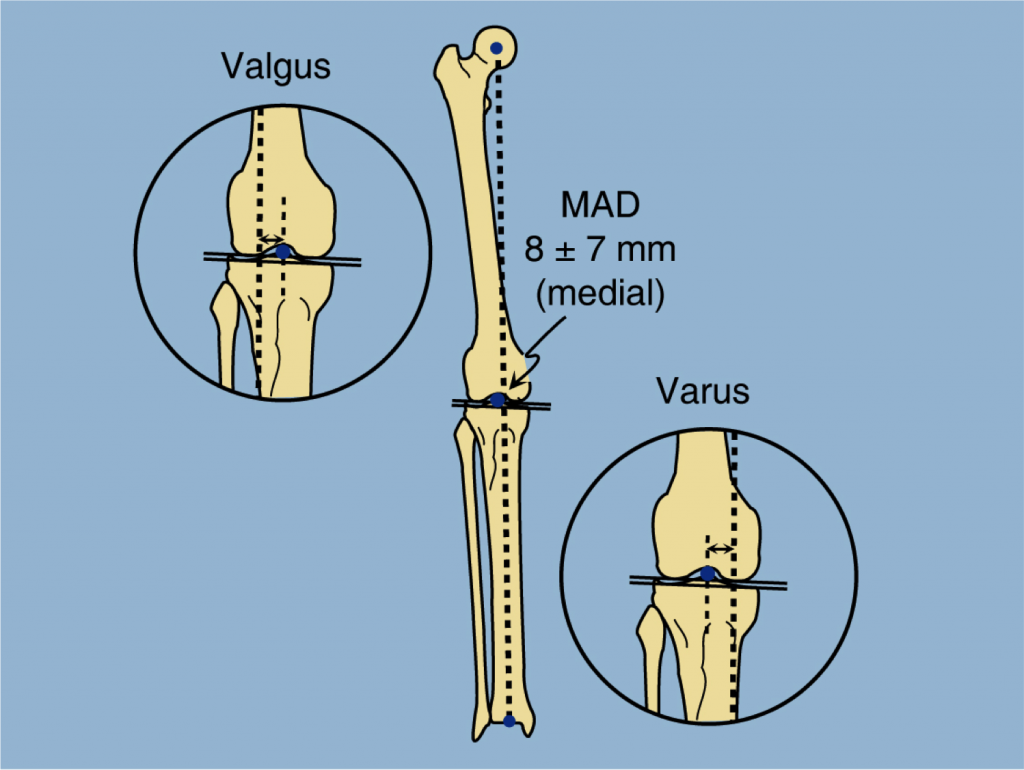

In normal alignment, there is a linear relationship between the femoral head in the hip joint, the center of the knee joint, and the center of the ankle joint; one can draw a straight line between the three joints. When there is a deformity in the lower extremities, the line between the femoral head and the ankle joint will not pass through the center of the knee joint. When the center of the knee is lateral (toward the edge) to the line between the femoral head and the ankle, there is a varus deformity; when the center of the knee is medial (toward the middle) to the line between the femoral head and the ankle, there is a valgus deformity (also known as "knock knee").

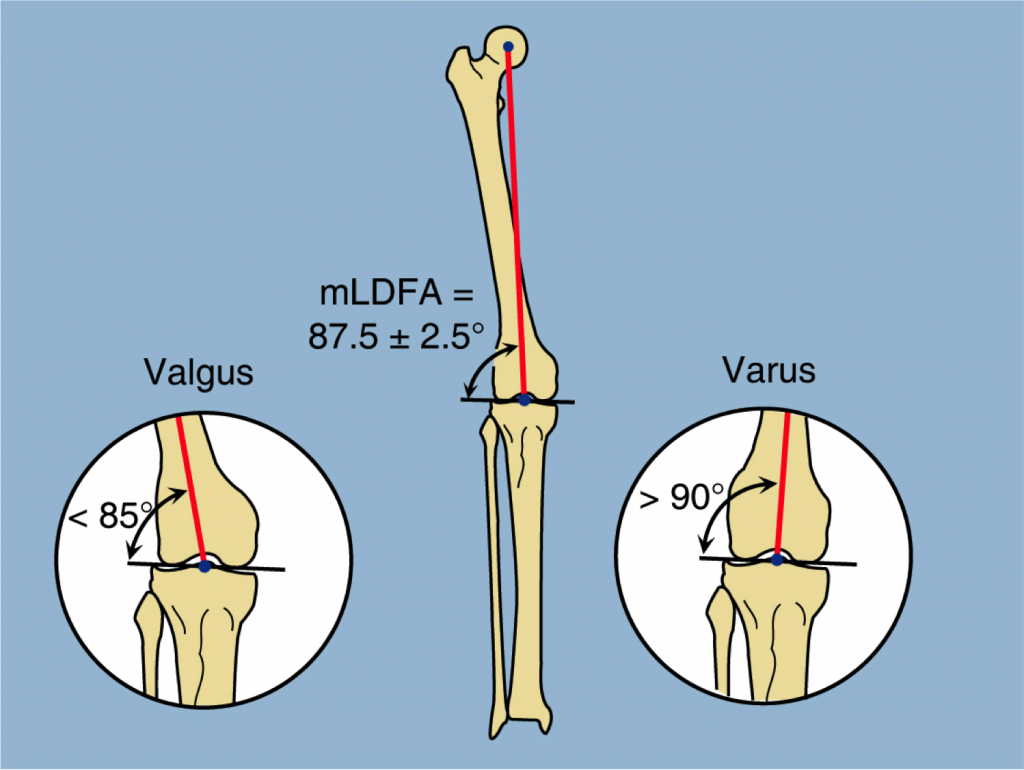

Another way of measuring varus and valgus knee deformities is by measuring the angles between the center of the knee joint and the center of the tibia and / or femur. In normal alignment, the angle between the center of the knee joint and the middle of the femur is 87.5 ± 2.5°. When there is valgus deformity, this angle is less than 85°; when there is a varus deformity the angle is greater than 90°.

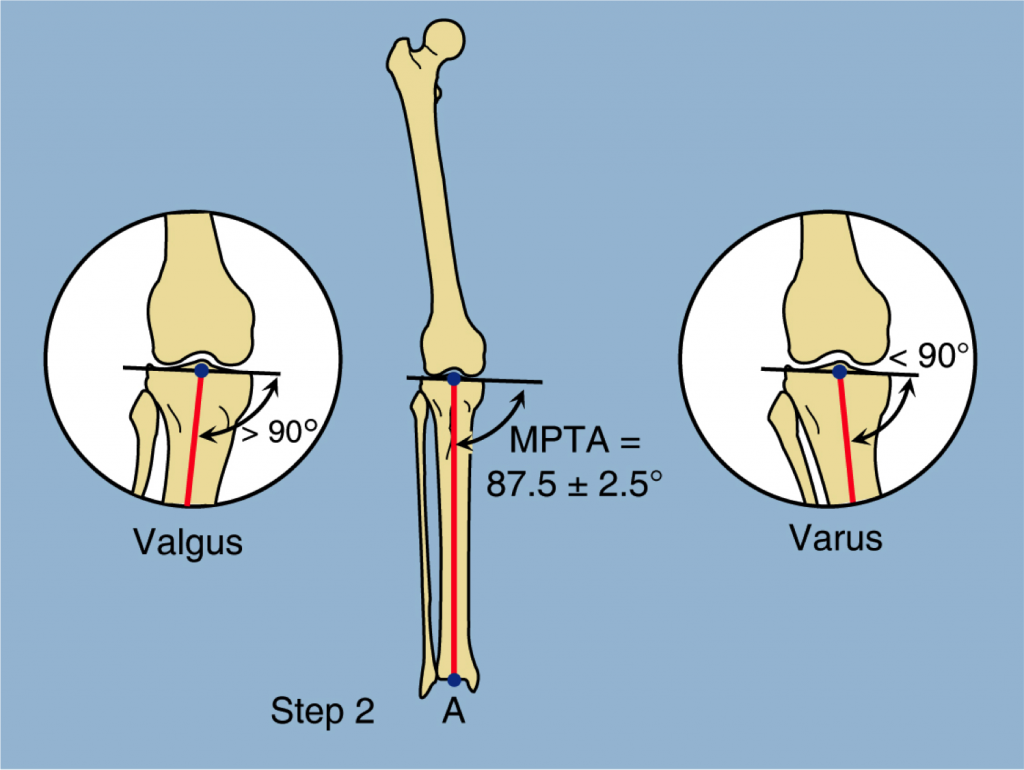

One can also measure the angle between the center of the knee joint and the center of the tibia. In normal alignment this angle is also 87.5 ± 2.5°. When there is valgus deformity, this angle is greater than 90°; when there is varus, this angle is less than 90°.

Infantile Blount's Disease

Infantile Blount’s disease refers to Blount’s disease occurring under four years of age. Children present with an obvious bow leg deformity and internal tibial torsion. The challenge is to separate true Blount’s disease from normal physiologic varus. Most children have mild varus (bow legged deformity of their knees) in the first couple of years of life. Towards the third year of life the knees straighten out and may become a little bit knock-kneed (valgus). This is the normal cycle for the lower limbs.

During that first two years of life, excessive bow leggedness may lead to suspicion of Blount’s disease. It is often difficult to distinguish the two. Various angles are used to measure the relationship of the shaft of the tibia to the upper growth plate of the tibia (Levine Drennan angle). If this angle is greater than 11 degrees it usually indicates Blount’s disease.

Rickets can also masquerade as Blount’s disease. Rickets deformities lead to bow leggedness and must be distinguished from Blount’s disease since the treatments are completely different. Rickets deformities are related to either a deficiency of vitamin D in the diet or a genetic cause that leads to vitamin D metabolism disorders and is related to kidney disease. Therefore when observing such patients, a metabolic profile (blood test) including calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase and vitamin D levels are obtained. It is important that this test be done prior to the patient eating to get the correct phosphate level. One can easily be fooled on phosphate levels which can make the difference of diagnosis of one of the most common type of rickets (hypophosphatemic rickets).

Once Blount’s disease is identified and diagnosed by ruling out physiologic varus and rickets and possibly other dysplasia causes (e.g. achondroplasia, hypochondroplasia), then considerations for treatment should be given early.

The etiology of infantile Blount’s disease is considered to be a developmental disorder. This means that the patient is not born with this condition. It is not a congenital condition. It develops during growth. The most prevalent theory regarding Blount’s disease development relates to early weight bearing and early damage to the growth cartilage of the upper tibia. One of the classic studies on this was performed by Golding in Jamaica who identified that children who developed Blount’s disease started walking earlier than children who did not develop Blount’s disease. The other common predisposing factor is race. Blount’s disease has a much higher prevalence in patients of sub-Saharan African racial origin. Golding’s classic study was predominantly in black children in Jamaica. This is not to say that Blount’s disease is not seen in children of all races. In fact, the classification of severity of Blount’s disease is named after a Finnish orthopedic surgeon named Dr. Langenskiold. Dr. Langenskiold’s study was predominantly on white children.

What seems to occur in Infantile Blount’s Disease is damage to the growth cells in the developing cartilage of the upper tibial growth plate. Normally, the middle of the growth plate receives a greater load than the edges. This is true in children and adults. The more bow legged or varus deformity there is the loading is even higher. Since children normally start with a bow legged position they predispose themselves to overloading the inside of the knee. Since there is very little bone to protect from such load at an early age, damage can occur to the medial growth plate.

It is ironic that most parents encourage their infants to start jumping and weight bearing using various devices that allow infants before walking age to take load (such as a jolly jumper). If they knew about the etiology of Blount’s disease perhaps they would refrain from such unnecessary ambulation at this age. The earlier a toddler starts walking, the earlier they start loading the medial growth plate. This puts them therefore at higher risk of developing Infantile Blount’s Disease because there is less bone in the upper tibia at such a young age, making it more fragile.

Treatment for Infantile Blount's Disease

Juvenile Blount's Disease

Most Juvenile Blount’s disease is really Infantile Blount’s Disease diagnosed after the age of 4. It is not common for Blount’s disease to really begin at this age, but it is probably left unrecognized until it is picked up at some age prior to adolescence. The mechanism of Blount’s disease is the same as described above in the infantile section. The difference is that since there is much more in the epiphysis of the tibia and since the condition has been around for longer, there is a greater likelihood that there is a more severe manifestation of Blount’s disease.

The Langenskiold classification grades the degree of Blount’s disease. It represents the degree of damage to the upper tibia with the higher-grade degrees having complete closure of the medial aspect of the growth plate of the upper tibia. With the increasing grade of deformity, the lack of development of the medial tibial plateau is also evident and appears as either a “pagoda tibia” or a depressed medial plateau. The failure of the medial growth plate to develop leads to a loss of height of the medial side of the knee and a sloping of this medial tibial plateau. On an AP x-ray, it appears as an inclined tibial plateau highest towards the center of the knee and lowest on the medial side thus giving the appearance of a pagoda or arrow-head shape.

Because the medial collateral ligament attaches lower down on the upper tibia, this loss of height on the medial side leads to a pseudo instability of the knee. There is apparent laxity of the knee joint to examination and when the patients walk they describe a wobble in their knee joint. To the observer, there is a sudden jerky bend to the knee every time they take a step. This is referred to as a “lateral thrust.” This lateral thrust adds to the varus deformity. In other words, there is a bony deformity combined with a soft tissue or knee laxity deformity. By the juvenile stage, the deformity of Blount’s disease is much more complicated than it was in the infantile stage.

Treatment for Juvenile Blount's Disease

Adolescent Blount's Disease

Adolescent Blount’s Disease is a separate entity from the infantile type. While Juvenile Blount’s Disease usually arises in infancy, the adolescent type is usually obesity related. In the adolescent type, damage occurs to the medial tibial physis. Since the medial tibial epiphysis is fully ossified, there is no damage to that structure and the pagoda tibia described above does not occur. Therefore, in Adolescent Blount’s Disease, it is more of metaphyseal varus or metaphyseal varus and flexion or metaphyseal varus and internal rotation. Joint laxity is not usually a major component. Leg length discrepancy may be an issue in Adolescent Blount’s Disease. The treatment of Adolescent Blount’s Disease is a proximal tibial osteotomy for angular correction plus or minus lengthening and derotation.

Treatment for Adolescent Blount's Disease